The Supreme Court has recently clarified how standard form employment contracts—typically drafted by employers and offered on a take-it-or-leave-it basis—should be interpreted under Indian law. These contracts often leave employees with little to no bargaining power, but the Court has laid down specific legal rules to balance this power.

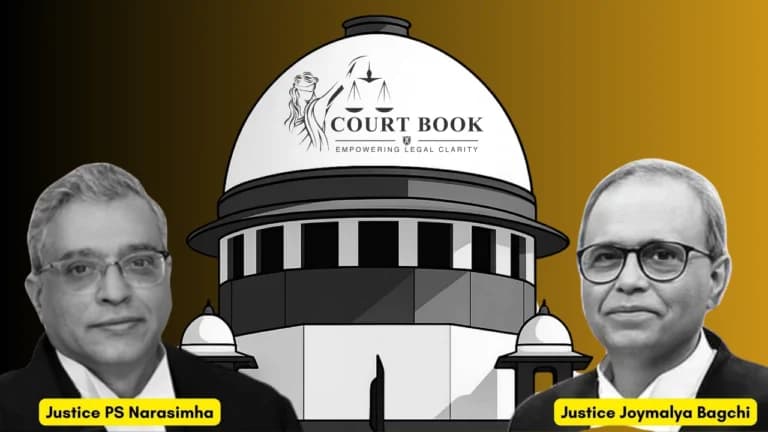

A bench of Justices PS Narasimha and Joymalya Bagchi ruled that such contracts, while creating an inherent power imbalance, are not automatically illegal. However, they must be examined carefully when challenged.

Read also: Supreme Court Declares Maharashtra’s Zudpi Jungles as Protected Forests, Mandates Strict

The Court summarised the principles for interpreting these contracts as follows:

- "Standard form employment contracts prima facie evidence unequal bargaining power."

- "When the weaker party (employee) claims undue influence, coercion, or that a term is against public policy, the Court must examine it carefully, considering the parties' unequal status and the contract's context."

- "The burden to prove that a restrictive covenant is fair and not against public policy lies on the employer (covenantee) and not the employee."

The case arose when a bank imposed a ₹2 lakh penalty on a Senior Manager (MMG-III) who resigned early—before completing the mandatory three-year service—so they could join another bank. The employee challenged this clause, claiming it was unfair and restrictive of trade under Section 27 of the Contract Act.

Read also: Supreme Court Criticizes Indian Navy Over Denial of Permanent Commission to Woman JAG Officer

Initially, the High Court sided with the employee, saying the clause was a restrictive trade practice. But the Supreme Court reversed this decision. It ruled that such clauses don’t restrict an employee from taking up future employment but merely impose a financial consequence for leaving early.

"A plain reading of clause 11 (k) shows restraint was imposed on the respondent to work for a minimum term i.e. three years and in default to pay liquidated damages of ₹2 lakhs. The clause sought to impose a restriction on the respondent's option to resign and thereby perpetuated the employment contract for a specified term. The object of the restrictive covenant was in furtherance of the employment contract and not to restrain future employment. Hence, it cannot be said to be violative of Section 27 of the Contract Act."

The Court also rejected the employee’s argument that the penalty clause was unfair because it was part of a standard-form contract with no room for negotiation. It emphasised that the public sector bank needed to retain skilled staff and that early exits imposed significant costs on the bank.

Read also: "In Personal Liberty Cases, High Courts Must Act Swiftly": Supreme Court Grants Bail After 27

“The appellant-bank is a public sector undertaking and cannot resort to private or ad-hoc appointments through private contracts. An untimely resignation would require the Bank to undertake a prolix and expensive recruitment process involving open advertisement, fair competitive procedure lest the appointment falls foul of the constitutional mandate under Articles 14 and 16.”, the Court observed.

The Court concluded that the ₹2 lakh penalty was reasonable, especially considering the employee’s senior position and attractive salary package.

In summary, the Supreme Court’s decision clarifies that while standard form contracts often favour the employer, they are not invalid unless proven to be oppressive, unconscionable, or against public policy. Employers bear the responsibility to prove that restrictive clauses are fair and justified.

Case Title: Vijaya Bank & Anr. VERSUS Prashant B Narnaware