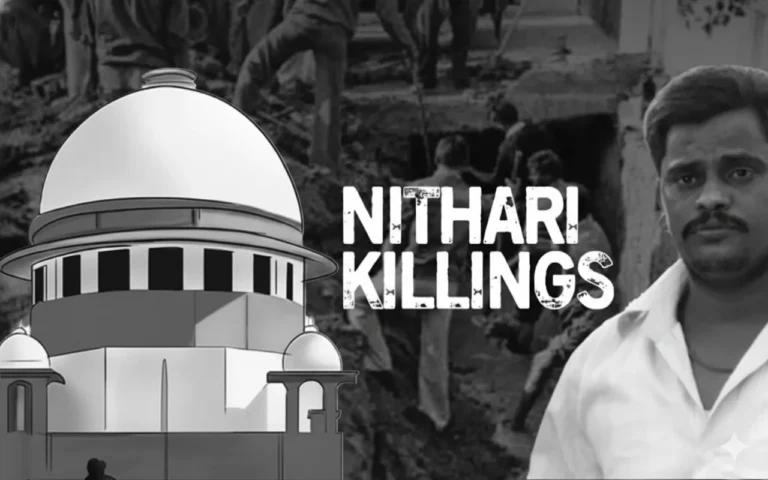

In a landmark verdict that will likely reshape India’s understanding of “curative justice,” the Supreme Court on Tuesday acquitted Surendra Koli once dubbed the “Nithari serial killer” after finding that his conviction rested on evidence the Court itself had later rejected in identical cases. The three-judge bench led by Chief Justice Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai, and Justices Surya Kant and Justice Vikram Nath, said that “two sets of outcomes resting on the same evidentiary foundation cannot lawfully coexist.”

The bench invoked its curative jurisdiction, an extraordinary legal power used only when grave injustice survives all other remedies. “When final orders of this Court speak with discordant voices on an identical record, public confidence is shaken,” Justice Vikram Nath wrote, adding that intervention here was “not an act of discretion but a constitutional duty.”

Background

The case traces back to the grisly Nithari killings between 2005 and 2006, when several children and women disappeared near House D-5 in Sector 31, Noida owned by businessman Moninder Singh Pandher. Koli, Pandher’s domestic worker, was arrested after human remains were found around the premises.

In 2009, a Ghaziabad court convicted Koli for the murder of 10-year-old Rimpa Haldar and sentenced him to death. The Allahabad High Court upheld the sentence, and the Supreme Court affirmed it in 2011, calling the case “rarest of rare.” His review petition was dismissed in 2014, though his death penalty was commuted to life imprisonment by the High Court a year later.

However, between 2010 and 2023, Koli faced twelve more trials based on the same confession and same recoveries. In October 2023, the Allahabad High Court acquitted him in all those cases, calling the evidence “coerced, inconsistent, and scientifically uncorroborated.” The State’s appeal was dismissed by the Supreme Court in July 2025. That left an irreconcilable contradiction: Koli stood acquitted in twelve cases but convicted in one despite the same evidence base.

Court's Observations

The Supreme Court found this inconsistency intolerable.

“The object is not to reopen evidence as in a second appeal,” the bench explained, “but to cure a manifest miscarriage of justice where inconsistent results persist on the same foundation.”

The Court noted that Koli’s confession under Section 164 of the CrPC was recorded after nearly sixty days of police custody without proper legal aid. The magistrate, it said, failed to certify that the confession was truly voluntary.

“The Investigating Officer’s proximity to the recording process compromised the environment of voluntariness,” the bench observed.

It further highlighted that recoveries of bones and clothes, which the prosecution relied upon, were made from open areas already known to the public. Excavation had begun before Koli’s alleged “disclosure,” disqualifying it as valid discovery under Section 27 of the Evidence Act.

On the forensic front, searches of the house did not reveal any human blood or remains consistent with multiple murders. The DNA tests only proved the identity of victims not who killed them.

“Science aided only identification; it did not prove authorship of homicide,” the Court clarified.

Justice Nath remarked that these lapses were not mere technicalities but went to the root of fairness.

“Article 21 of the Constitution insists on a fair, just, and reasonable procedure,” the bench said, stressing that such fairness must be “at its acutest where capital punishment is imposed.”

The judgment bluntly stated:

“To allow a conviction to stand on evidentiary basis that this Court has since rejected as involuntary or inadmissible in the very same fact-matrix offends Article 21.”

Court's Decision

Concluding that “the confession is legally tainted” and the recoveries unreliable, the Supreme Court declared Koli’s conviction unsustainable. The bench recalled and set aside its own 2011 judgment affirming his death sentence, as well as the 2014 dismissal of his review plea.

“Criminal law does not permit conviction on conjecture or a hunch. Suspicion, however grave, cannot replace proof beyond reasonable doubt,” the bench emphasised, while acknowledging the agony of victims’ families and the investigative failures that “corroded the fact-finding process.”

The Court directed that Surendra Koli be released immediately, if not required in any other case, and instructed the Registry to inform the concerned jail and trial court for prompt compliance.

Before concluding, the bench reflected on the larger institutional failure:

“Negligence and delay corroded the fact-finding process and foreclosed avenues that might have identified the true offender,” the judges wrote.

“Each lapse weakened the reliability of evidence and narrowed the path to truth.”

With this, one of India’s most sensational criminal cases came to an unexpected end not with final punishment, but with judicial correction and a reminder that the rule of law must prevail even in the darkest of crimes.

Case Title: Surendra Koli vs State of Uttar Pradesh & Another